“While [African music] admits of being discussed,

it cannot be strictly defined” – Andre Craddock-Willis

It is impossible to fix one cultural antecedent as the ancestor of Hip Hop music but we can identify that it springs from the rich and complex history of African American music and expression. As a result, both the musical and lyrical performers of Hip Hop- the MC/rapper and the DJ/producer- draw from a seemingly endless well of direct and indirect sources. In the words of Afrika Bambaataa, Bronx, NY Hip Hop pioneer:

|

| Afrika Bambaataa |

|

| The definitive first study of Afro-American music |

“...the music of the Negro in America, in all its permutations... [reveals] something about the Negro's existence in this country as well as something about the essential nature of this country, i.e. society as a whole.” (from Blues People Introduction, 1963)

As African Americans encountered the wonders of modernity or the lingering oppression of slavery and institutional marginalization, the ability to account for these experiences were often lyrically expressed. Thus, these experiences were expressed with grave seriousness in the work of African American preachers, revolutionary orators such as Malcolm X or Gil Scott Heron or the soul crooners like Sam Cooke.

Skat singers like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald or early rhythm and blues performers like Louis Jordan offered a more worldly expression that still bore links back to West African music and traditions. And while particularly ribald, the "toasts" of the early 20th century displayed a verbal, lyrical rhythm while spinning a tall tale born from an actual event. Below, a prison "toast" of the story of the legend of Stagger Lee

Clearly, in a wide variety of forms, African American cultural history has its share of oratory masters. Hip Hop MCs and rappers have been influenced and informed by all of these traditions. The first “Masters of Ceremony”- the hosts of the first Hip Hop parties in the Bronx in the mid 1970s- adopted both the preacher's power and a toaster's rhymed wit. These previously styles of speak and slang were twisted into a vocal performance at Bronx parties known initially as MCing and later called rapping. The following briefly discusses the "Black American" musical influences of the 1950, 60s and 70s that had the most immediate impact on the sound of Hip Hop in 1973.

The Genius, Disc Jocks and Mr. Dynamite

|

| Ray Charles |

In "Towards An Aesthetic of Popular Music" Simon Frith theorizes that modern genres of popular music are shaped by the technologies that create and disseminate them. With this in mind, it must be emphasized that the music of Ray Charles' contemporaries and successors was regularly received by audiences via radio during this period. As popular forms of rock and R&B grew in popularity and stature, the experience of this music was often framed by the talents of the local disc jockey. Sociologist Todd Gitlin speaks of how DJs in the 1960s shaped listeners experiences:

[The DJ] invaded the home, flattered the kids’ taste (while helping mold it), lured them into an imaginary world in which they were free to take their pleasures… …the disc jockeys played an important part in extending the peer group, certifying rock lovers as a huge subsociety of the knowing.

Standouts in the field always did this with a flair and change of speak. Douglas "Jocko" Henderson, a popular DJ in Philadelphia and New York City during the 1950s and 60s used jive and slang while on air, granting his radio show character and status that was as entertaining as the music itself. A sample of Jocko Henderson’s broadcast style as he speaks between songs:

"Soul Travelin'" by Gary Byrd is a musical example of the DJ's charisma and narrative power over the music.

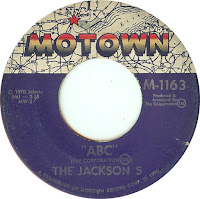

During the 1960s and 70s, R&B music and their artists grew in profile. Detroit's "Motown Sound" enjoyed both a large white and black audience and represented the first largely successful black owned record label. The wider acceptance of "soul" music was reflective of the racial upheaval that began with the 50s Civil Rights Movement and Motown label owner Barry Gordy's purposeful streamlining of his artists' sound.

|

| James Brown |

Embodying both the dirtier, funkier sound of Stax and the immense popularity of Motown was James Brown. The Hardest Working Man in Show Business, Soul Brother #1, the Godfather of Soul, Mr. Dynamite became the most prolific black soul singer of the late 1960s, dominating R&B charts and pop charts alike. Risking his commercially privileged status, Brown also made considerable efforts to champion the "Black Power" movement of the 1960s and 70s in his music ("Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud") or as a an instrument of peace during the riots following Martin Luther King, Jr's assassination. Brown's impact on Hip Hop and popular soul and dance music at large is undeniable.

As Brown's musical career expanded in the 1970s his band the JBs in both sound and lyrics reflected the plight of the urban cities. Lyrically, songs like "Get on the Good Foot" spoke of limited economic opportunity, while "The Payback" was tough anthem for street hustlers. Musically, Brown and the JBs created beats stripped of orchestration, emphasizing rhythmic improvised interplay between singer, drummer, bassist, guitarist, organ, and horn players. "Think" by Lyn Collins, one James Brown's leading divas, showcases the JBs penchant for danceable grooves and provoking lyrics.

The JBs live show stunned audiences with unyielding volume and energy. With unworldly fervor, James Brown's famous 1964 "T.A.M.I." show may be the best and most astonishing example of this:

For Hip Hop music, Brown and his bands provided innumerable rhythmic backdrops; as an African American icon he personified both an inspirational success story and the first example of a pioneering "Black owned" entertainment franchise that made decisions on its own terms.

"All of the Above"

Digging beyond just the "popular Black music" of the 1960s and 70s, further roots of Hip Hop are found in Jazz, African American literature, and the Black Arts Movement of the period. In particular, the more confrontational stance of the 1960s Black Power movement produced rhythm and poetry that bore similarities to rapping in the Bronx in the 1970s. The Last Poets and Gil Scott Heron were the most notable performers of this type of "rap." But, in regards to lyrical content, Hip Hop would not realize these types of subjects in a definitive fashion until the 1980s and 1990s.

Digging beyond just the "popular Black music" of the 1960s and 70s, further roots of Hip Hop are found in Jazz, African American literature, and the Black Arts Movement of the period. In particular, the more confrontational stance of the 1960s Black Power movement produced rhythm and poetry that bore similarities to rapping in the Bronx in the 1970s. The Last Poets and Gil Scott Heron were the most notable performers of this type of "rap." But, in regards to lyrical content, Hip Hop would not realize these types of subjects in a definitive fashion until the 1980s and 1990s.

Other influences of the Hip Hop MC can be found in the outspoken explicit monologues and performances of black comedians such as Dolemite's "Signifying Monkey", Redd Foxx or Jimmie Walker. After all, what is an MC that isn't entertaining or have a sense of humor? Richard Pryor's "Flying Saucers" is evidence how stand up could be both profane and political, humorous and poignant all in a span of a short few minutes.

A jazz/soul comedian such as Millie Jackson with her “Phuck U Symphony" shattered any preconceived notions of how a woman should behave or even what genre or attitude a performer should conform to for popular acceptance. Again, the explicit content of rap music would not emerge until the late 1980s but these performers clearly had a swagger that the earliest MCs adopted when on stage.

Good Times

As for the Bronx Hip Hop DJ, the two turntable techniques employed by early pioneers such as Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa are owed to an underground music movement in which the DJ emerged as the center piece of the show: Disco. In 1970, on the fringes of mainstream society, this new music labeled "Disco" was being created not by musicians but DJs.

In NYC, Disco music began as dance parties thrown by DJs often in predominately gay neighborhoods in downtown Manhattan, Fire Island, and other small clubs. Early Disco was nothing more than an up tempo funk and soul recordings such as "Get Lifted" by George McRae.

Importantly, disco DJs "blended" records of the same tempo together for one continuous mix of unending night of dance music. The video below effectively showcases a seamless mix of early Disco records; take note of the transitions from song to song at :45 and 1:22 mark and so on. Disco became a DJ dominated genre of popular music, displacing the importance of the musician and elevating the DJ to the role of the artist and star performer.

|

| R&B singer Diana Ross in the DJ booth |

Exploring the "Roots of Hip Hop" continue here with a look at Jamaican Sound System culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment